Music Emerging from the Texts

While musical archaeology studies in the Mediterranean area and the Middle East have examined the physical evidence and iconography, written sources have always also played a key role. This was brought into the spotlight when, in the 1970s, Anne Kilmer, an Assyriologist at Berkeley, California deciphered a cuneiform document in the Hurrian language which had been excavated from Ugarit. This she identified as a Bronze-Age hymn which provided evidence of notation based upon a Mesopotamian notation system. Once presented in western notation, this musical excerpt could be heard by modern ears.

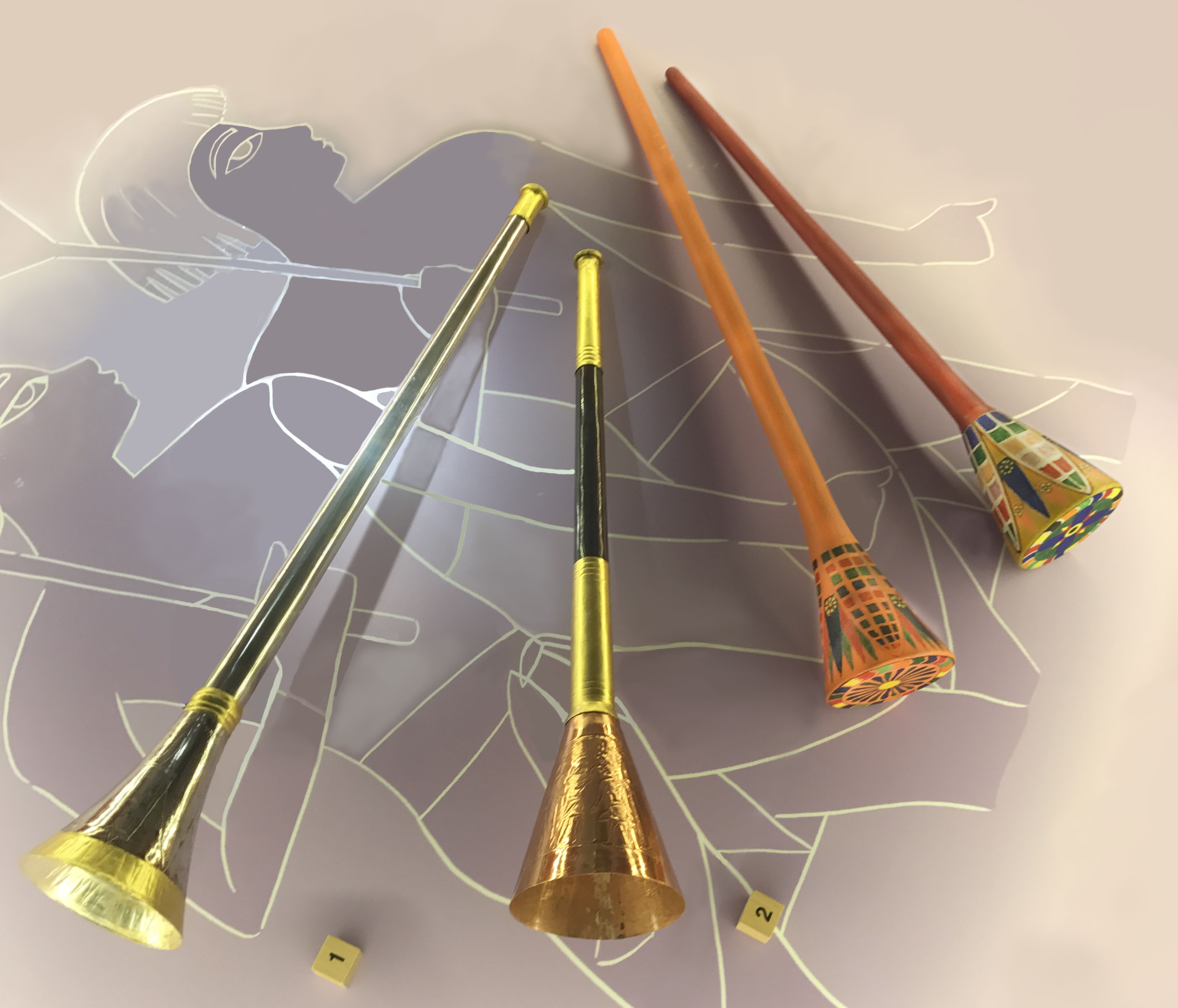

Since then, other similar identifications have been made of works from Egyptian and Greek times. While these may be seen by many as lying outside the scope of music archaeology, such a view depends upon one’s perspective. My view is that anything which provides a light which illuminates the past world of musical instruments must not be cast beyond our interest because of categorical niceties. Another development lies in the deciphering of an Egyptian papyrus by Alexandra von Lieven. In her report, she opens our eyes to the shenanigans that a pair of temple trumpeters have got up to when they appear in court. All such accounts help to build up a picture of ancient musicians.

Music of the Most Ancient nations

In 1864, Carl Engels, who had moved to London via Manchester from Germany wrote a book entitled The Music of the Most Ancient nations, particularly of the Assyrians, Egyptians and Hebrews with special reference to discoveries in Western Asia and in Egypt. Engels’ work looks at the instruments used by the peoples named in the book’s title and discusses in considerable detail what the musical notations of the time might have been. In this, he analyses all these from the perspectives of the times he lives in. He makes considerable use of analogies with the instruments and musical practices of the pre-industrial peoples then being visited by explorers and missionaries of the time.

As is normal for the time, Engels covers Biblical accounts of music, instruments and musicians and produced a listing of all the occurrences in the Bible. To emphasize his embedding in his time, when referring to the Assyrian trumpet, he points out that is is not around eight feet long like our trumpet, referring therefore to an instrument of Baroque trumpet length of eight-foot C. He then adds that the ancient version is without the recently-introduced auxiliary means of pistons and cylinders.

Horizontal Studies

Several works have looked at particular regions and provided valuable references for studying specific genres. One such work is Joachim Braun’s 2001 book on the instruments of Palestine and Israel.

Language: helper and Hinderer

A hazard met by researchers when working in the world of the Romans and Ancient Greeks lies in the language available to the writers and cross translations of these. From the perspective of a brass-instrument researcher, both the Greeks and the Romans suffered from a dearth of terms when it came to describing the instruments of their own and other nations. Unfortunately, we have to rely on some of these writings in Latin and Greek to some extent and many authors have give such texts undue credence. The Cumae frieze (my ref: IC498) depicts some seven different Native European brass instruments and stretches well beyond the capability of either Latin or Ancient Greek to describe them.